**The year 1979 etched itself into the annals of history as a pivotal moment for Iran, marking the dramatic downfall of a centuries-old monarchy and the rise of a new, theocratic state. The central figure in this seismic shift was Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, whose reign culminated in a revolution that reshaped the Middle East and continues to reverberate globally.** This article delves into the complex tapestry of events that led to the overthrow of the Shah, exploring the deep-seated grievances, political machinations, and cultural shifts that culminated in the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 stands as one of the most significant events in the modern history of the Middle East, leading to the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. It was a revolution born from a confluence of factors: widespread discontent over the Shah's autocratic rule, his ambitious but often disruptive modernization programs, the suppression of political dissent, and a growing religious fervor that found its voice in the exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Understanding this complex period requires a look back at the Shah's rise to power, the challenges he faced, and the forces that ultimately led to his dramatic exit from Iran.

Table of Contents

- The Last Shah: A Brief Biography of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

- The Pahlavi Dynasty: Modernization and Its Discontents

- The Gathering Storm: Seeds of Discontent

- The Escalation of Protests: A Nation on Edge

- January 1979: The Shah's Final Flight

- The Return of Khomeini and the Birth of the Islamic Republic

- The End of a 2,500-Year Monarchy

- Legacy and Lasting Impact of the 1979 Revolution

The Last Shah: A Brief Biography of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was the second and last monarch of the Pahlavi dynasty, a royal title, "Shah" (pronounced /fa/), historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies. He succeeded his father, Reza Shah, in 1941 amidst the tumultuous backdrop of World War II. Born in 1919, Mohammad Reza was groomed for leadership from a young age, receiving education in Switzerland before returning to Iran. His father, Reza Shah, as the first Pahlavi monarch, had determined to modernize and centralize the operations of Iran, using a Western model of industrial development. This legacy of modernization, coupled with an autocratic style of governance, heavily influenced Mohammad Reza's own reign. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's rule, which began with the Allied occupation of Iran, saw him initially navigating a delicate balance of power. He was seen by many as a progressive leader who aimed to transform Iran into a modern, prosperous nation. However, his path was fraught with challenges, including internal political struggles and external pressures. The early years of his reign were marked by a significant power struggle with Mohammad Mosaddegh, a popular nationalist prime minister. This struggle culminated in Mosaddegh’s ouster in 1953, with help from the United States and the United Kingdom, an event that would cast a long shadow over the Shah's legitimacy and contribute to the grievances that fueled the later revolution. This episode solidified the Shah's grip on power but also sowed seeds of resentment among a populace that increasingly viewed him as a puppet of foreign powers. His ambition for Iran was undeniable, but his methods often alienated key segments of society, setting the stage for the dramatic events of 1979.The Pahlavi Dynasty: Modernization and Its Discontents

The Pahlavi dynasty, established by Reza Shah in 1925, embarked on an ambitious program to modernize Iran, drawing inspiration from Western models. This vision was largely continued by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The heart of the Middle East antiquity, the first Persian (Iranian) Empire, had a long and rich history, but the Pahlavis sought to propel Iran into the 20th century. Reza Shah quickly instigated a system of industrial development, infrastructure building, and secularization, laying the groundwork for his son's more expansive reforms. While these efforts brought about significant progress in areas like education, healthcare, and infrastructure, they also created deep social and economic disparities, alienating traditionalists, the religious establishment, and a burgeoning class of intellectuals and urban poor.The 1953 Coup and its Lingering Shadow

A pivotal moment in Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's reign, and a significant precursor to the 1979 revolution, was the 1953 coup d'état. This event saw a power struggle between the Shah and his popular nationalist Prime Minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, who had moved to nationalize Iran's oil industry, much to the dismay of British and American interests. The data explicitly states that a power struggle between him and Mohammad Mosaddegh led to the latter’s ouster in 1953, with help from the United States. This foreign intervention, orchestrated by the CIA and MI6, solidified the Shah's authority but irrevocably damaged his image among many Iranians. It fueled a perception that the Shah was a pawn of Western powers, undermining his legitimacy and fostering deep-seated anti-Western sentiment. The memory of 1953 lingered, becoming a powerful symbol of foreign meddling and an argument against the Shah's rule for future revolutionary leaders. The coup effectively removed a democratic voice and paved the way for the Shah to consolidate absolute power, setting the stage for increased repression and a lack of political outlets for public grievances.The White Revolution: Progress and Polarization

In the 1960s, the Shah launched what he termed the "White Revolution," a series of far-reaching reforms aimed at modernizing Iran's economy and society. These reforms included land redistribution, nationalization of forests and pastures, the sale of state-owned factories to finance land reform, electoral reforms, and the establishment of a literacy corps. While some aspects of the White Revolution were genuinely progressive, such as increasing literacy rates and expanding women's rights, they were implemented top-down, without genuine public participation or consent. The land reforms, for instance, often benefited large landowners and created a new class of landless peasants who migrated to overcrowded cities, leading to social dislocation. The secular nature of many reforms also deeply offended the powerful Shi'ite clergy, who saw them as an assault on Islamic values and traditions. The Shah's lavish celebrations, particularly the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire in 1971, further highlighted the growing chasm between the opulent royal court and the struggling masses, fueling accusations of extravagance and insensitivity. This period of rapid, often jarring, modernization created a deeply polarized society, laying fertile ground for the revolution that would ultimately depose the Shah of Iran in 1979.The Gathering Storm: Seeds of Discontent

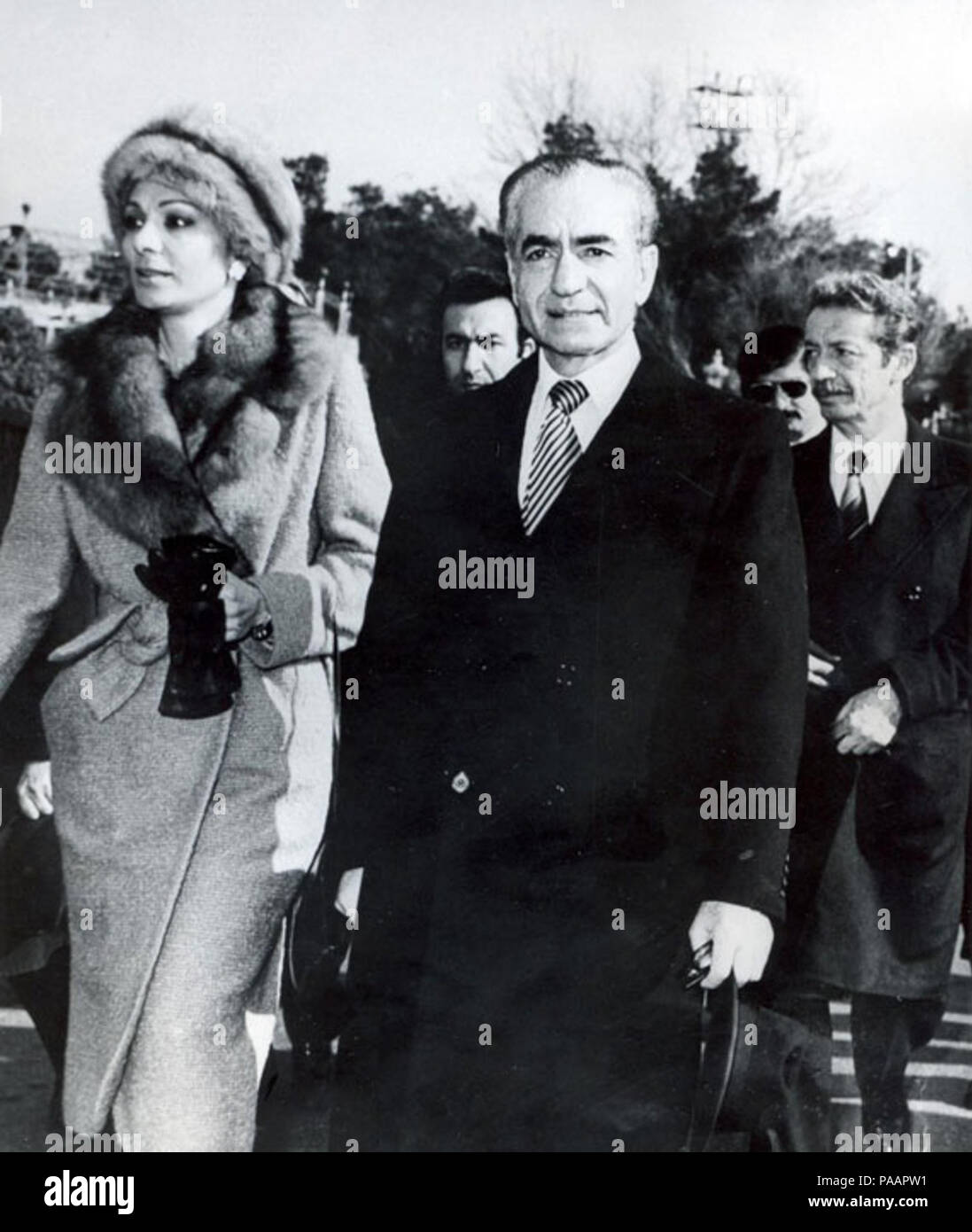

Despite the Shah's efforts to project an image of a modern, prosperous Iran, beneath the surface, widespread discontent was simmering. His autocratic rule, characterized by a powerful secret police (SAVAK) that suppressed dissent through arbitrary arrests, torture, and executions, alienated intellectuals, students, and human rights advocates. Political parties were largely banned, and freedom of expression was severely curtailed, leaving no legitimate channels for grievances to be aired. The rapid economic growth, fueled by oil revenues, was unevenly distributed, leading to stark wealth disparities. While a small elite prospered, a large segment of the population, particularly in rural areas and urban slums, struggled with poverty and lack of opportunity. Furthermore, the Shah's close ties with Western powers, particularly the United States, were viewed with suspicion by many Iranians, especially after the 1953 coup. His perceived subservience to foreign interests, coupled with the cultural Westernization that accompanied his modernization drive, was seen by religious conservatives as an erosion of Iran's Islamic identity and sovereignty. The religious establishment, led by figures like Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, capitalized on these sentiments, portraying the Shah as an un-Islamic ruler beholden to the West. The Shah's personal life, including his marriage to Empress Farah, while seemingly modern, was often perceived as out of touch with the traditional values of a significant portion of the population. This confluence of political repression, economic inequality, and cultural alienation created a volatile environment, where even minor incidents could ignite widespread unrest. The stage was set for a revolutionary uprising that would ultimately culminate in the dramatic events of 1979.The Escalation of Protests: A Nation on Edge

By the mid-1970s, the simmering discontent in Iran began to boil over into open protests. These demonstrations, initially sporadic, grew in intensity and frequency throughout 1977 and 1978. Students, intellectuals, and a growing number of religious figures spearheaded the movement, drawing in broader segments of the population. The protests were fueled by a combination of factors: economic hardship, particularly high inflation and unemployment; political repression, with calls for greater freedoms and an end to SAVAK's brutality; and a strong desire for cultural authenticity, rejecting the Shah's Westernizing policies. Each protest, often met with brutal force by the Shah's security forces, only served to galvanize the opposition further, creating a cycle of violence and retribution. Key events, such as the killing of student protesters in Qom in January 1978, followed by a series of mourning ceremonies that transformed into anti-Shah demonstrations, escalated the crisis. The traditional Shi'ite mourning cycle, occurring every 40 days, provided a ready-made calendar for sustained protests across the country. The "Black Friday" massacre in September 1978, where security forces opened fire on demonstrators in Tehran's Jaleh Square, killing hundreds, became a turning point. It shattered any remaining illusion of the Shah's ability to control the situation peacefully and convinced many that his regime was irredeemable. The army, once the bedrock of the Shah's power, began to show signs of internal dissent and reluctance to fire on its own people.The Role of Religious Leadership and Ayatollah Khomeini

Central to the escalating protests and the ultimate success of the revolution was the charismatic leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Exiled by the Shah in the 1960s for his outspoken criticism of the White Revolution and the Shah's ties to the West, Khomeini became the spiritual and political leader of the opposition from afar. From his exile in Iraq and later France, he skillfully used cassette tapes and telephone calls to disseminate his fiery sermons across Iran, circumventing the Shah's censorship. His messages resonated deeply with the masses, particularly the urban poor and traditional segments of society, who saw him as a champion of justice and Islamic values against a corrupt and oppressive regime. Khomeini's vision of an Islamic government, free from foreign influence and based on religious principles, offered a compelling alternative to the Shah's secular monarchy. He successfully united disparate opposition groups—from liberal democrats to leftists and religious conservatives—under the banner of Islamic revolution. His unwavering resolve and moral authority provided a clear direction for the movement. As the protests intensified, Khomeini's calls for the Shah's overthrow grew louder, transforming the movement from one seeking reforms into a full-blown revolution demanding the end of the monarchy. The religious networks, including mosques and bazaars, became crucial organizational hubs for the revolution, facilitating communication and mobilization that the Shah's regime struggled to counter. The power of Khomeini's leadership proved instrumental in shaping the Iranian Revolution of 1979.January 1979: The Shah's Final Flight

By late 1978 and early 1979, the situation in Iran had become untenable for Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Faced with an army mutiny and violent demonstrations against his rule, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the leader of Iran since 1941, was forced to flee the country. The protests had paralyzed the nation, with strikes crippling the oil industry and government services. International pressure mounted, and even his closest allies, including the United States, began to withdraw their full support, recognizing the inevitable. The Shah's attempts to form a civilian government and make concessions came too late; the revolutionary tide had become irreversible. On January 16, 1979, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a weeping king driven from his kingdom, flew his royal jet out of Iran on a journey from which he would never return. The Shah of Iran had fled the country following months of increasingly violent protests against his regime. Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi and his wife, Empress Farah, left Tehran and flew to Egypt, marking the end of his 37-year reign. This moment was captured by international media, symbolizing the dramatic collapse of a once-powerful monarchy. For many Iranians, it was a moment of euphoria and liberation, the culmination of years of struggle against an autocratic regime. For others, particularly those who had benefited from the Shah's rule or feared the unknown future, it was a moment of profound uncertainty and sorrow. In January 1979, the Shah left Iran, ending 2,500 years of monarchy, a lineage that traced back to the ancient Persian empires. His departure created a power vacuum that would quickly be filled by the revolutionary forces led by Ayatollah Khomeini, setting the stage for the next phase of the Iranian Revolution.The Return of Khomeini and the Birth of the Islamic Republic

The departure of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in January 1979 opened the door for the triumphant return of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. After more than 14 years in exile, Khomeini returned from exile in February, specifically on February 1, 1979, to a rapturous welcome in Tehran. Millions poured into the streets to greet him, seeing him as a messianic figure who would usher in a new era of justice and independence. His return marked the swift transition from the Shah's monarchy to an Islamic revolutionary government. The interim government appointed by the Shah quickly crumbled, and the military, demoralized and fractured, declared its neutrality on February 11, effectively sealing the fate of the old regime. Within days of Khomeini's return, the foundations of the Islamic Republic of Iran were laid. Revolutionary committees (Komitehs) sprang up across the country, enforcing the new order and meting out revolutionary justice. A provisional government was formed, and a referendum was held in March 1979, with an overwhelming majority voting to establish an Islamic Republic. This swift transition reflected the depth of public support for Khomeini and the revolutionary movement, which had successfully mobilized the masses against the Shah's regime. The revolution, which overthrew Shah Pahlavi, established the Islamic Republic of Iran, fundamentally altering the country's political, social, and cultural landscape.Establishing Strict Islamic Law and a New Order

With the establishment of the Islamic Republic, Khomeini and his followers moved quickly to implement their vision for Iran, enforcing strict Islamic law. This meant a dramatic shift in societal norms and governance. Women were required to wear the hijab, alcohol was banned, and Western cultural influences were systematically purged. The legal system was reformed to align with Sharia law, and revolutionary courts were established to try and punish those associated with the former regime. Many former officials, military leaders, and even some secular opposition figures were executed or imprisoned. The new government also embarked on a path of "Neither East, Nor West, Islamic Republic," distancing itself from both the United States and the Soviet Union. This anti-imperialist stance, coupled with the enforcement of Islamic law, redefined Iran's international relations and its internal dynamics. The revolution's impact was immediate and profound, transforming Iran from a monarchy with aspirations of Western-style modernity into a unique religious state, whose influence would extend far beyond its borders, particularly in the Middle East. The changes ushered in by the Iranian Revolution of 1979 were comprehensive, touching every aspect of Iranian life and setting the country on a new, distinct trajectory.The End of a 2,500-Year Monarchy

On the 11th of February 1979, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, was officially overthrown as a result of the Iranian Revolution. His overthrow saw the definitive end of the 2,500-year-old monarchy, a continuous line of royal rule that had shaped Persian history since antiquity. This was not merely a change of government but a fundamental reordering of Iranian society and its identity. The institution of the Shah, which had been a cornerstone of Iranian political and cultural life for millennia, was dismantled, replaced by a system based on the principles of Islamic jurisprudence and the concept of *Velayat-e Faqih* (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), with Ayatollah Khomeini at its apex. The fall of the monarchy was a symbolic rupture with Iran's imperial past, and a clear rejection of the Shah's vision of a secular, Westernized nation. The transition was swift and decisive, leaving little room for a counter-revolution. The symbols of the monarchy were removed, palaces were repurposed, and the very concept of hereditary rule was denounced as un-Islamic. This profound shift marked a definitive break from a long and storied history of kings and emperors, fundamentally altering Iran's self-perception and its place in the world. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 thus represents not just a political upheaval, but a cultural and historical turning point, closing a chapter that had spanned over two and a half millennia.Legacy and Lasting Impact of the 1979 Revolution

The Iranian Revolution of 1979, which led to the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, left an indelible mark on Iran, the Middle East, and global politics. Its legacy is complex and multifaceted, characterized by both profound achievements and significant challenges. Internally, the revolution brought about a new political system based on Islamic principles, transforming Iran into a unique theocracy. It empowered religious institutions and figures, leading to significant social and cultural changes, including the enforcement of Islamic dress codes and the reorientation of education and media. While it brought an end to autocratic rule and foreign influence, it also led to new forms of authoritarianism, with limited political freedoms and a suppression of dissent, particularly against the new religious establishment. Regionally, the revolution sent shockwaves throughout the Middle East, inspiring Islamist movements and challenging the existing order of secular monarchies and republics. It fueled the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), a devastating conflict that cost millions of lives and reshaped the geopolitical landscape. Globally, the revolution fundamentally altered Iran's relationship with the West, particularly the United States, leading to decades of strained relations, sanctions, and proxy conflicts. The hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy shortly after the revolution solidified this adversarial relationship. The revolution also contributed to the rise of political Islam as a potent force on the international stage, influencing movements from Lebanon to Afghanistan. The Shah of Iran's downfall in 1979 remains a critical case study in modern history, demonstrating the power of popular mobilization, the fragility of seemingly stable regimes, and the profound, long-term consequences of political and social upheaval. Its impact continues to be debated and analyzed, shaping contemporary discussions about governance, religion, and international relations in the 21st century.Conclusion

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 stands as a testament to the power of popular will and the profound consequences of an autocratic regime losing touch with its people. The overthrow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, was not a sudden event but the culmination of decades of simmering discontent over political repression, economic inequality, and cultural alienation. From the 1953 coup that solidified the Shah's power with foreign assistance, to the ambitious but polarizing White Revolution, and finally to the relentless protests galvanized by Ayatollah Khomeini, each stage contributed to the inevitable downfall of the 2,500-year-old monarchy. The Shah's final flight in January 1979 marked the end of an era and ushered in the Islamic Republic, a radical transformation that reshaped Iran's domestic and international trajectory. This pivotal moment continues to influence geopolitical dynamics, serving as a powerful reminder of how deeply intertwined history, religion, and politics can become. Understanding the complexities of the Iranian Revolution is crucial for comprehending the modern Middle East. What are your thoughts on the legacy of the Iranian Revolution? Share your perspectives in the comments below. If you found this historical deep dive insightful, consider sharing it with others who might be interested in this transformative period. Explore more articles on our site to continue your journey through pivotal moments in world history.Related Resources:

Detail Author:

- Name : Reinhold Emard

- Username : kulas.mitchel

- Email : audreanne.rath@schowalter.com

- Birthdate : 1979-06-27

- Address : 371 Alberta Ports Nickolasland, ME 83768

- Phone : (918) 892-6460

- Company : Anderson and Sons

- Job : Rough Carpenter

- Bio : Repellendus nam molestias non sapiente culpa. Vel ea voluptatem voluptatibus hic. Nihil velit dolorem quisquam nisi. Ea voluptates perspiciatis eligendi aut.

Socials

facebook:

- url : https://facebook.com/nmorar

- username : nmorar

- bio : Et rerum architecto minima modi in. Qui blanditiis eveniet nihil minus.

- followers : 3183

- following : 2114

tiktok:

- url : https://tiktok.com/@morar2023

- username : morar2023

- bio : Eligendi eos consequatur ut.

- followers : 702

- following : 2073

linkedin:

- url : https://linkedin.com/in/ned_morar

- username : ned_morar

- bio : Eum dolor tempora eveniet voluptates quos sed.

- followers : 6833

- following : 566

instagram:

- url : https://instagram.com/ned.morar

- username : ned.morar

- bio : Recusandae aut est velit incidunt quidem. Accusamus voluptatem eos inventore facilis id.

- followers : 3898

- following : 418

twitter:

- url : https://twitter.com/ned.morar

- username : ned.morar

- bio : Nihil facere in sit quis. Incidunt maiores maiores minima aut exercitationem. Est porro ut eligendi vel possimus iste quia.

- followers : 5040

- following : 1259